I’ve always felt that I should hate advertising. After all, shouldn’t I resent the TV spots and magazine blow-ins, the billboards and subway placards, the online banners and popups, all the devices the world’s media planners have devised to manipulate me and sell my “eyeballs”? Shouldn’t I resist being made to participate almost involuntarily in the economic conquests of corporate players whose interests I don’t share? And really, shouldn’t I be concerned for what all these commercial messages might be doing to me?

You might think that with these heady cries of resistance on the brain, I’d be a tough customer for the messages themselves. I thought I was. As an adult, anyway, I had learned to see through the ruse of advertising and reject it. Then one night, on the eve of a summer vacation with my wife, I found myself inexplicably craving a bottle of Corona with lime. As I’m the type to favor real, craft beer if I can get it, this craving for Corona was exceptional, indeed. More exceptional still was the fact that the object of my craving — that bland bottle of golden soda water with a wedge of sour fruit in it — did not disappoint.

This anecdote is a small part of a larger story, a story fabled in marketing circles: that is, the story of Mexican brewer Cervecería Modelo’s Corona beer brand and its rise to prominence in the American beverage market. A light, unremarkable beer eschewed in its domestic market, Corona has become a textbook example of how an inferior product can nevertheless win loyal customers and market share through effective marketing.

“Miles Away From Ordinary”

In these days of wane for traditional media advertising, Corona’s “Miles Away From Ordinary” ad campaign seems almost quaint. While most marketers are looking to guerrilla and viral techniques to spend less and circumvent the kind of instinctive consumer ad resistance I expressed above, Corona simply blanketed the mass media — from 30-second spots on primetime TV to graphic wraps on the trucks of their distributors to those banner-flying planes that buzz up and down the Jersey Shore in summer — with the visual and aural sensations of a subdued tropical beach, a picture always completed by that iconic Corona bottle and obligatory lime wedge.

These images emerge from the kind of idle mental play that only occurs to a vacationing mind.

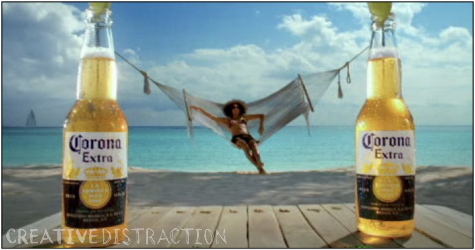

Whether in Web, TV, print and outdoor media, Corona ads consistently offer a flight of the senses to an idyllic, tropical place “miles away” from our ordinary worries and woes. Beach scenes and ocean sounds are powerful triggers of the so-called “relaxation response” — some psychotherapists use these exact tools to help patients cope with anxiety. The Corona drinkers in these scenes silence their cell phones and engage in other stress-neutralizing activities. A trope in the ads is the use of the Corona bottle in fanciful optical experiments: a bikini-clad woman appears to swing on a hammock between two Corona bottles (pictured); a beer-drinking beach-goer re-positions his Corona bottle to block his view of less attractive neighbors; a crescent moon over tropical waters appears in the mouth of a Corona bottle as if it were a lime wedge. These images emerge from the kind of idle mental play that only occurs to a vacationing mind.

All of these media ladle onto us, day after day, the promises and meanings of the Corona brand: namely, that drinking Corona is tantamount to a temporary escape, a vacation, from the punishing, daily fray of our ordinary modern lives. But how could Corona beer itself, that sad drink, ever deliver on such a promise? How could I have enjoyed the stuff?

Alcohol content is certainly part of it. But I suspect the phenomenon also has something to do with what Baylor College of Medicine researchers found with Coke drinkers: that brand knowledge can have “a dramatic influence on expressed behavioral preferences and on the measured brain responses” to beverages. In other words, all those ad dollars spent by Coca-Cola over the years haven’t been just to persuade us to buy Coke; they’ve also been part of the content of the product experience.

The Stakes of the Debate

Traditional advertising is more than the annoying, overpriced, valueless dinosaur it sometimes seems to be. Done right, it supports the product experience, it makes the product better.

There’s reason for all of us, marketers and consumers alike, to take heed of the Corona example. Told one way, the story of Corona is that of a few clever marketers with their smoke and mirrors duping us repeatedly into buying an inferior product. Told another way, though, the story of Corona is that of the creation of a unique and powerful product experience — an inner Disneyland for a certain kind of customer — and one that is only possible through a through the brand’s saturation of the mass media with its images, messages and myths.

In the latter telling of the story, traditional advertising is more than the annoying, overpriced, valueless dinosaur it sometimes seems to be. Done right, it supports the product experience, it makes the product better. But traditional advertising now struggles mightily as its economic bases disappear. Newspapers and magazines were first, and TV will follow: the Wall Street Journal recently reported that both prices and media buys at the major television networks are down for the first time in years, partly due to the recession, partly due to the migration of viewers to the Internet.

As an entrepreneur and marketer for smaller concerns who can’t buy 30-second spots on television, maybe I’d feel some smug satisfaction at the death of traditional advertising and the leveling of the playing field it represents. But as a consumer, I should remember that the end of traditional advertising wouldn’t mean the end of the commercial persuasion industry.

All the major social media websites are already thoroughly infiltrated by parties with commercial interests. On Twitter and Facebook, we face a relentless barrage of brands and companies trying to have a “relationship” with us.

Instead, commercial persuasion activity re-emerges wherever the eyeballs are. And what does that look like? Take, for example, so-called “social media.” All the major social media websites are already thoroughly infiltrated by parties with commercial interests trying to spawn, steer or fabricate word-of-mouth promotion for their products and services. On Twitter and Facebook, we face a relentless barrage of brands and companies trying to have a “relationship” with us. And often, we don’t even know what’s marketing and what’s not, leading Rob Walker, author of the New York Times Magazine’s “Consumed” column, to coin the term “murketing.”

Sure, we’ll survive the growth of murketing and demise of traditional marketing. We’ll probably even discover some brands and products and people we like. But like any form of adaptive evolution, it’s change, not progress — We may lose something worth saving.